MetalEars - Headphone amplifier #19, with the right punch for down tuned, brutal and distorted guitars.

Features:

- parametric low punch

- almost parametric treble/presence sink

- excellent clean performance

- drives all headphones (Ri >= 15E)

- includes interesting measurements about epic amplifier design failures ;-)

- ...

Amplifier #19, the somehow different headphone amplifier design...

As a musician and engineer, I am not afraid of tone controls.

If you are, this is probably not the right place for you...

(Though MetalEars still is an excellent amplifier with all that tone-stuff removed...)

WARNING:

Do only connect (big) dynamic headphones.

In-ear plugs or other tiny stuff, including your ears, might take damage.

If your phones start to clip, decrease volume or bass boost immediately!

Hardware

Input and Filter Stage

The input connection, usually your CD, DAT, DVD or whatever-player, first hits C5 for

DC-decoupling, with a -3dB corner frequency of ~1.5Hz (C5, R4+R7). IC2, the first OPA134, only acts as an impedance converter, which is required for the next stage.

Filter Stage (low section)Some headphones, especially the "good ones", sound too bright for distorted guitars. If you want a treble/presence sink added to the circuit, fit R3L/R, R1, C1 and R2L/R. If you don't need this feature, leave all these components out and short IC2-6 with IC1-3. For the upcoming discussion about the bass-boost functionality, we simply assume that the upper part of the connection IC2-IC3 is not present or the potentiometer R3L is turned towards IC2. In the image on the right, Za and Zb represent the potentiometer with its middle tap shorted to ground via an impedance. Even without calculating the circuit, it is obvious that the output follows the input if the following conditions are met:

In all other cases, the output voltage can be calculated by:

With the potentiometer turned to the left (Za = 0):

Well, this looks familiar. Even with the presence of Za, we now have a standard non-inverting topology. By turning the potentiometer from the left to the right, the amplification V can be varied from V=1 to V=1+Zg/Z. If we replace Zg by a resistor Rg and Z by an inductor

the transfer function ua/ue (with Zb = 0) becomes

which represents nothing else but a first-order low-pass filter:

normalized transfer function, Rg = L = 1

Adding the potentiometer value(s) as a parameter to the complete formula,

With an additional resistor in series with the inductor, to limit the gain

and assuming that Rg = 10 * R (rest like above)

By changing the values for the inductor (L'=L, L'=L/5 and L'=L/20), the corner frequency can be varied:

With a little more clever settings for Rg and Zp, the potentiometer value, we get a more "exponential feeling". Turning the knob towards zero (left), results in a finer adjustment. A good starting point for doing so is to consider the gain with the potentiometer set to the middle:

With Zp = 3*Zg, the results are looking promising (and sound right while turning the baaad knob):

The most common setup procedure is to start with the highest frequency available, so you clearly can hear where the mids stop while turning the knob counterclockwise. At least, I prefer this method. The upper +3dB point is intentionally set to an outrageous frequency of ~2kHz. For a gain of ~20dB (Rg/R = 10), Rg set to 3k3 and a corner frequency of 100Hz, would require a giant inductor of ~5H:

Wow ;) And even for 2kHz, an inductance of ~260mH would be required. Obviously, there's no (practical) way of building such an inductor, but fortunately one can build an active circuit that simulates an inductor.

While a NIC creates a negative impedance, a gyrator, built of two NICs, can transform an impedance to its inverse. Placing a capacitor in there transforms it into an inductor:

With only a few uFs, quite large impedances can be built. As an alternative, not-that-perfect-circuits can do the same with a single amp. With a clever value selection all parasitic residuals can be neglected:

TYPE II:

The result is an inductor with a resistor of value R = Z1+Z2 in series with it.

Which results in the equivalent circuit:

With the alternative values applied (15n/1M):

...

Filter Stage (high section)This is not a serious (HiFi) tone control. Its for musicians and those that would like to damp the higher frequency components.

After all that LaTeX typesetting for the bass-boost section, I am going to skip these

for the treble/presence cut circuit. Although this part of the circuit can be left out, it might help limit the intense, bright sound some headphones produce. If you decide to left it out, replace potentiometer R3 with a wire.

...

AmplifierAlthough almost every amplifier can be attached to the filter stage, assuming an adequate gain (0..20dB, depending on the input signal of the signal source and the ratio of the "bass boost"), I wanted something new.

I never designed a headphone amplifier with nothing else but some opamps

in the last stage. I usually prefer transistors ;)

A single, standard amp does not provide enough power for low impedance cans (*1*).

But from all I learned during the last 18 designs, the only way of supporting all

headphones (in terms of output level, distortion, 82 other parameters and - well, "sound")

is to reduce the amplifiers output impedance (far) below 10 Ohms.

A common practice for obtaining more output is to put multiple amplifier stages in parallel,

each stage decoupled with a (lower) 2-digit resistance.

A true no-brainer. No additional components, simple to build, no additional noise components... Almost perfect!

"Almost?"

And no matter if we choose the left or the right design, which opamp is the best one? Let's find out... ...

OpAmp Tests

We'll start off with a standard non-inverting design. The opamp test circuit above offers two gain settings:

Notice that the input potentiometer (10k) was set to "maximum level" for the impedance converter and 1/16 of its value for the 24dB circuit, an additional handicap for the latter circuit (except CMRR). For all measurements:

All measurements were done with:

Well, there's something wrong here ;)

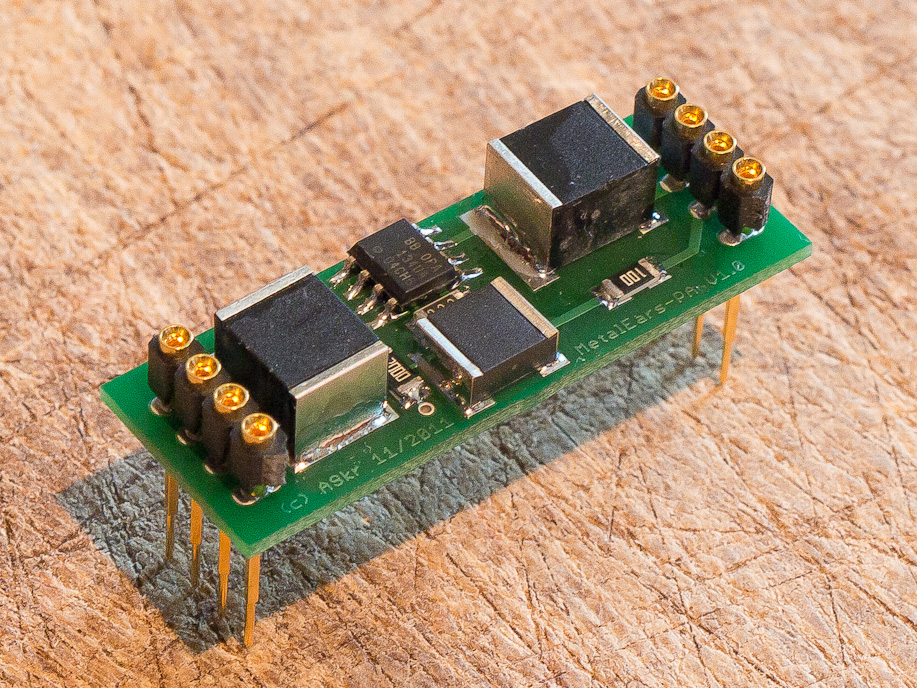

The final amplifier: XFEED-PAAll the insights derived from the previously measured data resulted in a brilliant power amplifier section with really excellent benchmarking data.

All measurements were done in the really not clean lab-environment (spikes at 50Hz, 300Hz-1k, etc...).

(((Insert stability stuff, right here...)))

Even with an outrageously large capacitive load of 100nF at the output,

everything remains stable.

...

Otherto be uploaded... |

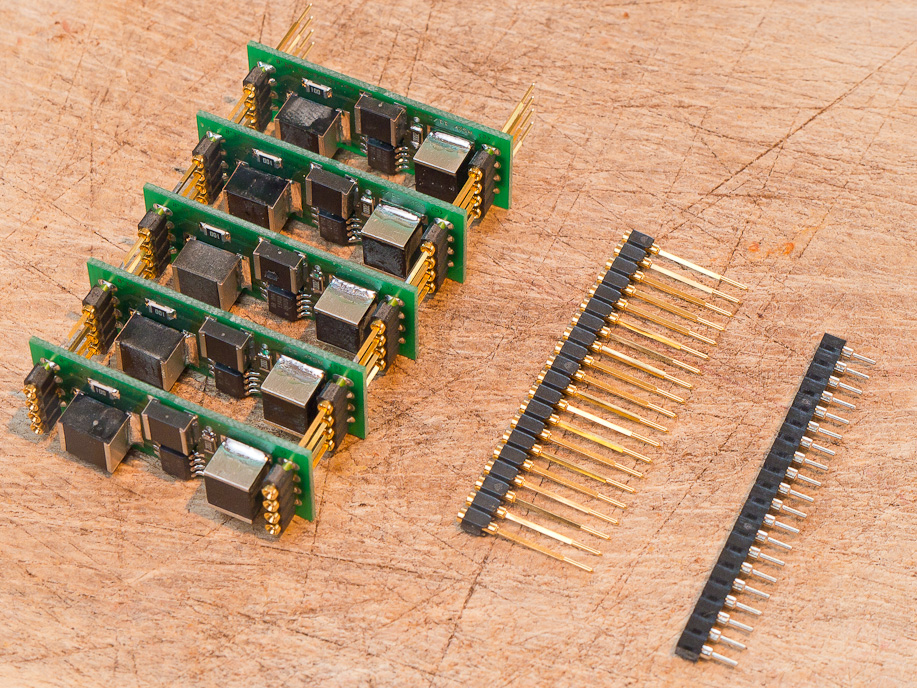

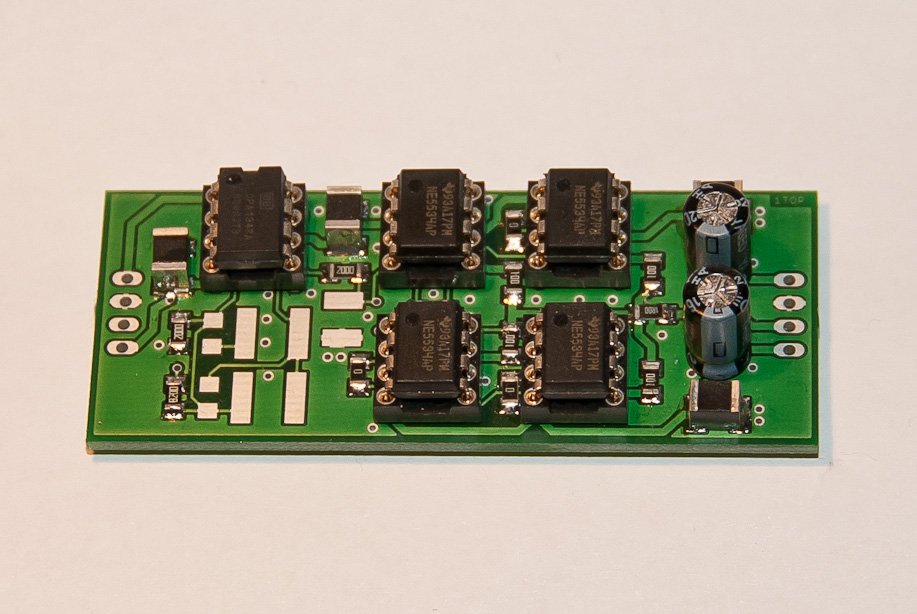

Some Useless Pics

|

|

Download

MetalEars:

Includes:

- several docs

- ...

DOWNLOAD: MetalEars_V13.zip Hardware, V1.3

DOWNLOAD: MetalEarsPA-XFEED_V10.zip Hardware PA-XFEED, V1.0

ASkr 11/2011: initial public release

ASkr 01/2012: added fun measurements and HW V1.2

ASkr 02/2012: found time to upload some PA-XFEED V1.0 docs

ASkr 04/2012: minor changes to the docs; removed some typos